“Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.”

-Arundhati Roy

On December 16, 2012, in New Delhi, a 23-year old physiotherapy intern, Jyoti Singh Pandey, was brutally beaten and gang raped in the private bus in which she was traveling with a male friend. Six men in the bus, including its driver, raped Pandey with an iron bar, beat her friend, then stripped them naked, and threw them from the bus. Pandey died from her injuries two weeks later in a Singapore hospital. The incident generated national and international coverage and was widely condemned in India and abroad.

The morning I heard the news of Pandey’s rape, something caught fire in me. A stark realization of the ongoing war between the masculine and the feminine, and how it is playing out on our planet, pressed on me like a physical force. I felt a burning desire to understand what was underneath the terrible violence that killed Pandey. I wanted to examine the rift between the masculine and the feminine that I suspected was at its source, and to contribute to its healing.

I have thrashed around in this wild and difficult territory for a long time, simmering in ancient memories of the brutality, degradation, and suppression that the feminine has endured on this planet. In the midst of my scalding inner turbulence about Pandey’s terrible death, I sensed a deeper intimation: another world is well and truly on her way, a world in which the voice, the intelligence, and the power of the feminine find their true place. My realization about this other world bubbled up from a deep well within me, and shook me to my core.

During my lifetime I have received many glimpses of the feminine way of knowing, of relating, and of being alive, but I did not embody them. Not even for a day. I was lost, an atom in the cosmos of my culture, in the wildly spinning, disembodied cyberspace that has taken over the earth. Like all of us, I am a child of the patriarchy; I wanted to ascend, to shine like the sun, to speed forward, to climb higher and faster than those around me. I carried that impulse into my spiritual life–until I reached the ceiling of my ascent, until all of my focused striving crashed into the wall of consequence and I fell off my glass mountain. My world shattered, and I fell headlong, a long way down.

Thanks to the grace of the feminine, I am still falling. I am embodying the sacred descent. Like the ancient Sumerian goddess Inanna, I have been called from heaven down into the underworld. In this mysterious kingdom I wander, learning the secrets of another kind of intelligence, one that was hidden to me before the fall. I realize now that ascent and descent are married to each other. As the contemporary spiritual teacher Thomas Huebl has said, “in our deepest humanity lies our highest possibility.” We are designed to grow in both directions, not to choose only one. I fell off my mountain because I lost my ground, my foundation. The body, the earth, the heart, the healing flow of water, called me back home.

yes, yes,

that’s what

I wanted,

I always wanted,

I always wanted,

to return

to the body

where I was born.

(Ginsberg, 1974-1980)

In my work in the field of death and dying, I have listened as people, approaching the end of their lives, flounder in the deep waters of disappointment, heartbreak and regret. I have been amazed at the grief many feel, looking back at how they lived, about losing touch with something crucial, something of great value. As I sit with more and more people making this sacred passage, I recognize a common thread weaving their regrets and sorrows together. One old man, during the last days of his life, illuminated that thread: “I lost touch with my humanity,” he said. “And after that, nothing felt right.”

I believe that an essential element that the feminine way of being can offer us is the reclamation of our sacred humanity. The feminine knows that life is sacred. Her all-embracing reverence includes everything; it is not reserved for certain aspects. She knows this with every breath, with every pulse of her heart, whether she lives in a male or female body. I have seen men brought to tears by the recognition of how this feminine energy, this consciousness, seeks to live in them. Sometimes they experience it in the form of the protector, the guardian, the warrior, who puts him on the line to serve and care for life. Consider the oppression, destruction, fragmentation and brutality that have resulted from culture’s obsessive ascent to the masculine. These devastations are all different faces of the same terrible loss; we have forgotten what it means to live with a true reverence for life. We are not yet fully human.

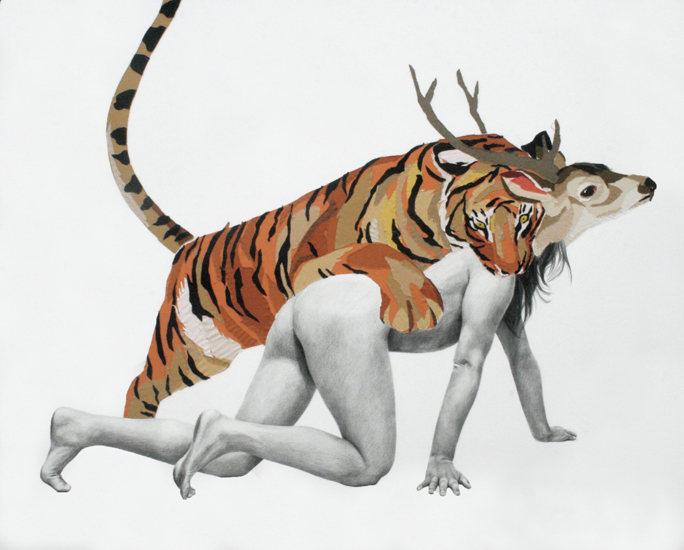

As we discover how to open ourselves to our deepest humanity, I envision an evolution in which the consciousness, energy, and force of the feminine and masculine together weave a healthy, living dynamic. The feminine and masculine are primordial, archetypal ways of being, difficult to contain within static concepts. We can speak of the feminine as the ground of being, the foundation of our existence, imbued with qualities such as receptivity, allowing, belonging, passion, and compassion. She is playful, flowing, mysterious, nourishing. She embodies the energy of the embrace and of descent. On an essential level, she is the principle of relatedness, of interconnection, of non-separation. Meanwhile, the masculine principle expresses the energy of ascent, and of penetration. It brings to life the qualities of will, integrity, focus, attainment, and perseverance. On an essential level the masculine is the principle of distinction, autonomy, and separation.

In many traditional spiritual teachings and practices, there is a tendency to lean into the feminine principle of non-separation, as if it were more evolved than the masculine principle. In these teachings, the masculine principle of separation is seen as a problem, something to be transcended or transformed. My current belief is that we need a more inclusive and integral approach to spirituality, and to life–one that recognizes the beauty and integrity of both principles. Neither principle exists without the other, and every human embodies both. The complex dance between the masculine and feminine has played out all over our planet for thousands of years, on the inner levels of our psyches and in the outer world.

The core of the struggle is much more than a simple conflict between the energy and consciousness of the masculine and feminine; it is more accurate to say that men and women, in many cultures and lineages, have fallen into distorted and unnatural ways of embodying both the feminine and the masculine. We have not been guided, taught, nor initiated into a mature, loving, and fully alive way of embracing these two fundamental ways of being alive. I have been amazed by the force of my desire to heal the deep gash between the masculine and the feminine. I spoke with a colleague recently about the possibility of a global emergence of the feminine. She said, “Well, she is rising now, that’s clear. Not fully, yet, but we feel her presence. And she’s not going to go back underground this time.” Her words resonated deeply within me. I felt their truth as a full-body, joyous awakening.

The post-modern world in which most of us live has exiled the essential depth and sacred nature of the feminine from our everyday life. We have not been able to participate in an ongoing experience of its healing and liberating power. For this reason, I think it can be helpful, and sometimes catalytic, to learn from indigenous people about living in direct contact with the feminine. I don’t believe that our collective healing and evolution will happen through a return to ancient ways of living. But we can receive a great deal through learning about the perspectives of people who were rooted in a way of life that deeply honoured the feminine.

In her book, The Continuum Concept (1977), Jean Liedloff transmits an amazing picture of the Yequana of Venezuala, a culture deeply grounded in an instinctive alignment with the deep nature of the feminine. Inge Bolin also wrote an exquisite ethnography about the people she lived with for over ten years in the high Andes, at sixteen thousand feet, calling theirs a culture of respect (2010). A member of the Siksika Blackfeet/Sauk people in Montana told me about how, when he was a young boy, he would wander freely between the groups of men and women in his village. He said that in all those years, he never heard a man speak of a woman as an object. When the men were together, if a woman’s name came up, she was spoken of with appreciation and praise. And it was the same when the women spoke of the men.

While the details of the lives they consider are different, Liedloff and Bolin both offer a vivid and moving picture of a people immersed in a way of being that is almost unfathomable to the western mind. These people live at the very edge of survival, often going without food for days, enduring intense hardship and challenge. Yet they demonstrate a profound trust in the sacred and unique intelligence of every human being, and a deep gratitude for the gift of life. They live with a constant sense of reverence for that which is greater than them: that which holds and sustains them. Their thinking, their behavior, and their values are not rooted in separation and isolation, the default positions in our post-modern culture. There is little loneliness, punishment, or coercion in their cultures. The people are attuned to something, rooted in something, that guides and nourishes and gives them strength, vision, and courage. They have their own names for what this is. I call it the sacred feminine.

Liedloff’s and Bolin’s descriptions of indigenous ways of life unwound something in me; they knocked me off my centre of gravity. I tossed and turned for many nights after reading their books, wrestling with a deep realization of our estrangement from the feminine and burning with a longing to embody the living experience of interconnection. The stories are transmissions of the deep love and respect that are possible in the space between men and women, parents and children, and in our own relationship with nature and the earth, if we only knew how to open ourselves to it. My heart claimed the possibility with fierceness and a strange kind of devotion, like a love for something incredibly precious that has been lost, that now wants to emerge in a new form, an updated version of itself.

What has happened, then, in the cultures where we have lost our humanity, our reverence for life, our capacity for empathy, deep feeling, tenderness, compassion, and courage? In order to penetrate into a deeper view, an insight that could begin to transform us in a real and lasting way, I began to explore the imprints we have received from our lineages about what it is to be a man or a woman. I have learned a lot about this conditioning, these inner structures of our psyche, from the people I have studied with. But I’ve learned the most from my own work.

I have worked for many years in the field of awakening and transformation, as a mentor, coach, teacher, and facilitator. I have been engaged with small groups, communities, individuals and couples. In all of the different dimensions of my work, my primary challenge has been the work with couples, be they heterosexual, gay, lesbian or transgender. In hundreds of sessions, I have been face to face with the fierceness of the conflict between the masculine and feminine. To sit with it, again and again, has been quite heartbreaking.

It is not so easy to illuminate the nature of this ancient conflict. One way to begin is to take a deeper look at the nature of awareness. Awareness, to most of us, means conscious awareness, light, and clarity. There is, however, another, quite different kind of awareness that we have been given. This is our feeling awareness, sentient awareness, the awareness of feelings, sensations and energy. In the evolution of our human history, the dominance of the conscious masculine dimension of awareness has eclipsed our capacity to access the feminine, intuitive, feeling side of our nature. In my perspective, this division between two core aspects of our humanity has created a primal split. I call it primal because it is so fundamental and so collective. We live inside it, with little perspective on what a different way of being human would look like, or how a culture that was not divided in this way would function. This division between the masculine and feminine expresses itself in each one of us, from a place where we have learned to instinctively dissociate from the depths of our own body and from our feeling awareness.

We inherit the split through our lineages, through all the ways in which we have been taught about what it is to be a man, to be a woman, to be a human being. These imprints have created structures in our psyches for thousands of years—deeply unconscious ways of thinking, perceiving, believing, and behaving. The image of a “real man” that most men in our culture inherit leaves no room at all for feelings, for tenderness, for open-hearted contact, or for vulnerability. In fact, many men who dare to display these qualities run the risk of experiencing violence and shaming at the hands of their fellow men.

Across the globe, most cultures flow from a consciousness that holds this core conditioning. My first vivid contact with this consciousness was when I was traveling through Arab countries in my twenties. I was haunted by the beauty, power, and intelligence I sensed in the women whose faces and bodies were hidden under dark veils. After living in India for twenty-three years, I discovered the same patriarchal conditioning, displayed in various ways, and arising from the same basic imprints. What kind of consciousness would create a culture that requires a woman to be burned alive on her husband’s funeral pyre? Imagine what has to be suppressed in the body and mind and heart of a human being for such a thing to happen, not just once, but as a tradition.

What have we inherited, both men and women, in the stream of our ancestral conditioning? We have been imprinted with the belief that a woman is a compliant, domesticated, objectified being, who serves and pleases, nourishes others, and sacrifices herself for those around her. Over the last few decades these images and deep imprints have been breaking down. As they dissolve, every woman embarks on her own journey of reclaiming her untamed, brilliant, powerful, and loving feminine essence.

Over the last fifteen years, I have met and worked with men and women who are daring to inquire into the conditioning that they have received. In group work that I’ve been a part of, the rage between the feminine and masculine has displayed itself. It is very sobering to encounter it face to face. It does not simply take the form of men lined up against women; the conflict is much more complex than that. Often the men come face to face with the intensity of their rage towards the patriarchy in their own lineages, and the damage that has been left behind. They can also encounter a profound anger towards the feminine, in themselves and in the world. And sometimes it is the women who rage against the feminine, as real contact is made with the truth of how much women have been subjugated, oppressed, and violated, and how much they have complied with living out the stereotype.

So here we find ourselves, in a world that desperately needs an evolutionary emergence of the feminine, with a vast amount of unintegrated trauma and rage sitting in the bodies, hearts, and minds of both men and women. In this inquiry into the emerging feminine, I am deeply curious about how women can begin to heal the individual and collective anger we carry in relation to the masculine. The energy of this anger can be turned against the masculine within us, or it can be a rage focused on the men around us. From years of experience working with both men and women, I feel that healing could begin with a deep and empathic understanding about what has happened to men at the hands of the patriarchy. It has occurred to me many times that the patriarchy may have been more destructive to the men on our planet than to the women, and that women could bring this wider and more compassionate perspective into our collective dialogue. I need to clarify that compassion does not mean submission. I am not encouraging women to continue to tolerate what they have already tolerated for too long. I’m speaking of an empowered empathy: “Do no harm and take no shit.”

Over the years, I’ve listened to hundreds of women speak about what it’s like to be partnered with someone who has not yet grown up. “I thought I had married a man,” they tell me, “and I am living with a boy. A boy who needs a mother, not a wife!” I know this feeling intimately, as I’ve lived inside this dilemma myself, more than once in my life. It is time for us to become responsible for our bitterness and our rage. It is time to stop criticizing and complaining. The healthy feminine, that freely embodies both masculine and feminine qualities, is madly, deeply, eternally in love with the masculine. She longs for him, wants to dance with him, to inspire him, and be protected by him. Raging at him is not going to create the alchemy needed. This anger needs to be welcomed, felt, and made fully conscious. In the fire of this wrathful compassion, there is love, wisdom, and an invitation that the masculine cannot refuse.

The secret of such alchemy begins with a radically new understanding of anger. We who love and long for the full emergence of the feminine need to begin embodying the fiery intelligence of healthy anger so that we can stand for ourselves, find our real will, and hold our boundaries. So that we can say no every time we need to say no. For a woman who has been brainwashed by the crippling image of the feminine ideal, this is a huge developmental task. To speak in her real voice, to express an honest no, feels deeply threatening to her and her relationships. So she often withholds her voice, stifles the energy of her no, and simmers in silent resentment until she finds the opportunity to nag, criticize and manipulate.

The sword that we need to pick up here is bright and beautiful. It is not a weapon to be used against a man. It is the sword of discernment, our keen awareness of the difference between healthy and unhealthy anger. When anger is distorted, it cuts, separates, and disconnects. It is meant to harm the other. We have all been led to believe that this is what happens whenever we are angry, so we have shut anger out of the circle of love. An extraordinary number of women have been taught that we must exile anger from our bodies, hearts, and minds in order to remain loving.

The transformation required is not a mental operation. It is a rewiring of the nervous system. When this rewiring happens I discover an amazing thing: when I am angry at you, I can contain the energy of anger, and remain connected with you at the same time. Instead of using anger to build a wall between us, or to hurt and punish you, I can use the energy of anger to care for myself and to connect more deeply with you. In the Buddhist teachings, this is known as the liberating energy of fierce compassion.

I cannot simply take all of the anger that has been stored in my body, including the anger I have inherited from my feminine lineage, and instantly transform it into this bright, fiery, loving

energy. It is a rigorous and profound process that takes its own sweet time. And it only happens in a context that supports such evolution. This context can be the strong and loving container of a relationship with a partner, elder, mentor, therapist, or teacher. It can also be a group of people deeply committed to this kind of exploration and discovery. If enough women could commit to this depth of healing, I think we could move together towards redemption of what has broken the feminine and masculine into warring camps within ourselves and between us.

There is one more aspect of this healing that I want to touch on. I first became aware of it when listening to Malidoma Somé, the African Indigenous teacher and shaman. He was speaking about an experience of being invited to a memorial ceremony at Arlington Cemetery in Washington for all of the people who died in war. Malidoma Somé was quite excited about attending the ceremony, knowing how much potential for healing exists in such gatherings. He turned up in his full tribal regalia, ready for something potent and mysterious to unfold. He stood patiently as the ceremony went on and on through many hours of cavalcades, songs, prayers, poems, and speeches. Finally, toward the end of the ceremony, he realized that it was going to end before any real grief had been expressed. He was astounded. “Oh my god,” he thought. “This culture really does not know how to grieve!”

Malidoma Some touches on a sore spot in our culture: we really do not know how to grieve, whether we are male or female. The medicine of grief is an important aspect of what the feminine has to offer us. Grief lives in the domain of feminine awareness, the part of us that is sentient, that knows how to hold the full intensity of feelings, and drop down into the earth and the water with our sorrow. The repressed grief in our culture is one aspect of why there is so much fire in the space between feminine and masculine. So much fire and so little water. The water of our tears is the precious medicine that is missing. “It is a terrible source of grief in itself, not to be able to grieve,” writes Martin Prechtel in his meditative investigation of grief and praise (Prechtel, 2015).

If we love the feminine deeply enough, if we long for her with enough real passion, we must be ready to grieve the loss of her, and learn, bit by bit, to feel and transform our ancient anger at the masculine into a love that can hold painful and disturbing emotions. It is an enormous challenge, and each one of us must decide whether or not we are ready to say yes. I offer what I have written here to the infinite field of possibility, with prayers that we can be moved and inspired by the death of Jyoti Singh Pandey, so that what she passed through contributes to our collective evolution. Her suffering is our suffering, and it could come to serve the immense beauty and power of the feminine. At this point, it is still a mystery as to how we are going to make our way into this new world. Perhaps, at this critical time in our human story, the feminine can lay her body and soul down, and rest deeply in the mystery, as she calls forth something new from the darkness.

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Great Nature has another thing to do

To you and me, so take the lively air,

And, lovely, learn by going where to go.

This shaking keeps me steady. I should know.

What falls away is always. And is near.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

Roethke, 1953

with love,

Shayla

Acknowledgements

I have been deeply impressed and informed in my work with anger by the teachings of Thomas Huebl. My gratitude to him is great. In my quest to bring compassion and understanding to the masculine, I have been supported and blessed by the work and the lives of Terence Real, Malidoma Somé, Robert Augustus Masters, Jayson Gaddis, Warren Farrell, Stephen Busby, and Robert Bly.

References

Bolin, Inge. Growing Up In a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2006.

Ginsberg, Allen. Collected Poems, 1947–1980. New York City, New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1988. [PERMISSION PENDING]

Liedloff, Jean. The Continuum Concept: In Search of Happiness Lost. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 1977.

Prechtel, Martín. The Smell of Rain on Dust: Grief and Praise. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 2015.

Roethke, Theodore. “The Waking.” The Poetry Foundation. Accessed September 14, 2015. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/172106

Roy, Arundhati. “Confronting Empire.” Text of a speech delivered at the World Social Forum, 2003. Outlook India (January 30, 2003). Accessed September 14, 2015. http://www.outlookindia.com/article/confronting-empire/218738

art credit: Ana Teresa Barboza

5 Comments

Join the conversation and post a comment.

It seems today we live in a phallic world and the dominant images are of money, power and technology. These characteristics are seen as gods to be worshipped. Love, beauty, sexual ecstasy, connection are not in the forefront.. The cure for this phallic world is the retrieval of the sacred feminine and the transformation of the inner world of the human being. We all have it within us to make choices regardless of our testosterone levels, embrace the masculine and feminine in all of us and bring the balance to order. But first we must explore the characteristics in each of us, understand our conditioning and recognizing this is not a war between men and women but a restoration of the sacredness in us all.

Thank you Shayla, for writing this article when you did, and for reposting it now. What resonated most for me today is the dichotomy our culture seems to have created between ascent and descent. Our collective energy is so focused on achieving, owning and moving forward that we have forgotten about being, sharing, and connecting. I am glad to see signs that more and more people are choosing to disbelieve these cultural myths and instead shape their lives around what matters to them most. Your writing gives me the courage to make that choice for myself as well.

Love, Natasha

this is a major piece of writing Shay, superb! so many points you make are worth each a chapter of thier own. I am pleased you bring in Martin Prechtel and his wholly unique and self standing offerings in grief. In my own orbit with a great deal of loss and accumulated grief in my life I have to agree with and emphasize this point, without a living capacity to grieve, to get messy in grief we are lost. My adopted country of Mexico knows how to grieve making the people and the place more ‘real’ and somehow more honest.

perhaps you have your reasons for not mentioning the ‘metoo’ movement in this rich piece on the battle between masculine and feminine, I am curious why. That you emphasize there is both in each of us I am grateful for, deescalating blame and shame in this struggle most welcome.

You bring hope and inspiration to the quest and a sense of the potential to celebrate both, together.

thank you – write on!

The clearest and most inclusive writing I’ve come across. Powerful. I hope many men and women read it!

Ok….was it really needed to be so graphic in the first few sentences of your article? It was extremely triggering and traumatizing for me and for people like me who have traumas related to this. It was very hard and destabilizing to read. Please be sensitive and compassionate in your writing. What was the purpose of being so graphic? Did you want to shock? Were you trying to purge yourself in some way? You can inspire and capture the hearts of your readers without the need to shock them.